- Home

- Martha Freeman

Strudel's Forever Home Page 2

Strudel's Forever Home Read online

Page 2

I meant to answer, but by this time Jake had unlatched the door to my kennel and I was licking his face. Then Shira clipped the leash to my collar, lifted me out and set me down. I tried to keep calm, but I couldn’t. I spun, I jumped, I spun some more. Soon my leash and I were tangled. Churro was laughing, then all the other dogs, too.

“What a ruckus!” said Shira. “Come on outside where we can hear ourselves think.”

Jake tucked me under his arm, and just like that, I left the small-to-medium-size-canine room for good.

“Goodbye, everyone!” I howled. “Maisie, I’ll miss you!”

“Strudel, quiet down!” Jake said. “Mutanski’s not gonna like it if you’re noisy in the car.”

“Moo-tan-skee?” Shira repeated the funny name.

“My mutant teenage sister, Mutanski for short,” Jake said. “People like my mom call her Laura. It’s Mutanski that drove me here ’cause my mom’s at work.”

“Well, that’s all right,” said Shira. “Your mom and I have already made the arrangements.”

By this time we were standing on the sidewalk outside the shelter. I hadn’t been there since the awful day I arrived, and a strange feeling came over me. The sky went dark. I felt exhausted and scared and sore. I began to tremble and cower.

Wise Maisie had told me about something called a flashback. It meant you remembered something so powerfully you lived it over again. Was I reliving the calamity? If I was, the view was in bits and pieces—rain, flashing lights, rough pavement against my paws.

“Strudel?” Jake said. “Hey, Strudel, what’s the matter, buddy?”

“Oh dear,” said Shira. “This used to happen to him sometimes when he first got to the shelter. Something bad must’ve happened before he came to us. Hey, boy? You okay?”

Jake’s and Shira’s voices seemed to come from far away. Gradually I became aware of Jake’s arms and ribs, of Shira’s fingers scratching me behind the ears. When I looked around, it was light—daytime. I didn’t hurt anymore. Everything was fine.

Shira said, “I think he’s coming around. Change can be unsettling for a dog, or for anyone. If there’s any trouble, you feel free to call us.”

Jake nodded. “Okay.”

A girl came up to us. She smelled like the greasy egg rolls she ate for lunch, as well as many polishes and lotions. She had paper-white skin, red lips and straight black hair.

“You must be Jake’s sister,” Shira greeted her.

“Mutanski,” Jake said.

The girl frowned. “I’m Laura,” she said to Shira. “Nice to meet you.”

Jake’s sister was nothing like Rachel Mae. Instead of lace and ribbons, she wore shorts, boots and a torn T-shirt. Her eyes were brown, not blue. Was she brainy? Hard to tell.

Shira wrapped me and Jake in a big hug and told us to take care of each other. There was a tear in her eye, and she wiped it with the back of her hand. “I’ve got to get back to work,” she said.

Mutanski pointed to a car parked at the curb. I don’t know much about cars, but I could see this one was old. There was a dent in the door, and the paint was coming off in patches.

“Backseat, you two,” Mutanski said.

Oh boy, oh boy, oh boy—car ride! I just love car rides!

And this car—wow! Did it ever smell delicious! Sweaty socks, spilled soda, the stale remains of greasy human snacks. Yummy!

I thought of my previous human’s car, which had smelled disgusting—almost as bad as the worst of all possible things, shampoo.

“You’ll be fine, won’t you, Strudel?” Jake pulled me close. “I bet you like car rides.”

I sure do!

“Strudel?” Mutanski started the motor. “You can’t be serious. Is that his name?”

“It’s his shelter name till I think of something else,” Jake said, “something brave-sounding. I know he’s small, but in his heart he’s a hero.”

Got that right!

Mutanski, meanwhile, was laughing like she’d never heard a better joke.

“Shut up!” Jake defended me.

“Don’t tell me to shut up. I am doing you a favor by driving you at all,” said Mutanski.

As the car pulled into traffic, I tried really really hard to be still, but I’d been cooped up a long time, and this was so exciting!

How could I resist dashing from window to window?

How could I help but greet the dogs I saw, and all the other creatures, too—creatures unlucky enough not to have been born dogs? On the streets outside the window now were horses pulling carriages. We must be in the Old West for sure!

“Sheesh, Jake, what is your mutt doing?” Mutanski shouted over my joyful barking. “Can’t you make him lie down?”

“Strudel—quiet!” Jake pulled me back into his lap. “Now let’s look out the window, okay? This neighborhood is called Old City. See the brick buildings? They’re hundreds of years old. That one is where the Declaration of Independence was signed. Our class took a field trip last year.”

“Oh great, teach your dog American history,” said Mutanski.

“You’re just embarrassed because he already knows more than you,” said Jake.

Mutanski’s answer was a snort. The car stopped and started again. It turned left, then right onto a wide boulevard. There were no more horses outside, just cars and people walking.

“If you’re so smart,” Mutanski asked her brother, “what’s that building there?”

“Uhhh . . . ,” said Jake.

“Ha!” said Mutanski. “It’s Old Swede’s Church, and it’s older even than Independence Hall. Some of the first Europeans to live in Philadelphia built it.”

“There were Swedish people in Philadelphia?” Jake said. “I thought only Italians, like Grandpa.”

“Swedes and Germans and Irish in this neighborhood—people from all over,” said Mutanski. “You’re not the only one who takes history in school.”

I looked out the window and saw a low building behind a long brick wall. It didn’t look special . . . except for one thing. It was familiar. Had I seen it before? Had I been here with my previous human? I couldn’t tell unless I smelled it; I couldn’t smell it from the car.

But the sight bothered me. When my human hadn’t come to get me at the shelter, I concluded he was gone and with him my home and everything else in my old life, too. Now here was something familiar. Was it possible I had been wrong?

There was no time to think more about it then, though. The car turned right onto another big boulevard, then left onto a narrower street.

“This is our neighborhood, Strudel. It’s called Pennsport,” Jake said. “And now we’re going down 2 Street. Every year around New Year’s, they have a big crazy party here. My grandpa is part of it—he’s what you call a Mummer. Have you ever heard of Mummers?”

Mutanski snorted again. “Give it a rest, Jake. Your dog doesn’t care about American history, or Mummers either!”

“How do you know?” Jake asked. “He likes stories, don’t you, Strudel?”

I do! I do! I do!

There were two more turns onto narrow streets before Mutanski twisted the steering wheel, backed up, twisted the steering wheel again. Finally we came to a stop.

“We’re here, buddy!” Jake opened the door and set me down on the sidewalk. “We had to park a couple blocks from home, but you like to walk, right? You’re a dog.”

Four

My first sniffs of my new neighborhood were not what I expected. I can’t claim I know exactly what a prairie smells like, but I was pretty sure it wasn’t this: well-fed pets, urban wildlife, greasy fast-food waste, flies and other bugs, gobs of sweet, chewed-up chewing gum flattened on the sidewalk.

As for the sounds: sirens, a basketball slapping asphalt, car horns and human voices yelling.

Where was the call of the whippoorwills?

So much for wide-open spaces.

I reminded myself that Jake had never actually said his home place was like Chief’s. I had

imagined that part myself. I decided to follow Maisie’s advice: I would live in the present, not the past—and that meant getting busy and learning all I could about my new neighborhood. A dog gets information through his nose, so as Jake and I walked, I stopped at every bush, tree, post and corner.

Unlike my previous human, Jake was not used to walking a dog. Soon he became impatient and tugged the leash. “Come on, Stru. Let’s go! We haven’t got all day, you know.”

Mutanski looked back over her shoulder. “Already complaining? I knew you weren’t responsible enough to have a dog.”

After that, Jake let me stop whenever I wanted. Soon I learned that my closest canine neighbors were both males, one a poodle and the other a Staffordshire terrier, which is the breed more commonly called a pit bull.

Both these dogs were big, a lot bigger than me. The poodle was about my own age and the terrier much younger, hardly more than a puppy. There was more information in their scents, too. The poodle was an independent type, not part of anyone’s pack, while the pit bull was timid, maybe even a coward. If I had to guess, I’d say he was bullied by his littermates.

I was checking out a fresh marker from the poodle when Jake tugged at me again. “This is it, Strudel,” he said, “your brand-new home. My mom’s at work, but she’ll be here for dinner.”

I had been replying to the scent the poodle had left on the dirt surrounding a spindly tree at the curb. Now I turned around and looked at my new place.

It was not a cottage with a front porch on the lone prairie. It was what’s called a row house—brick, three stories high, no space between it and the houses to the right and left. Two concrete steps led to the stoop and then a black front door. Mutanski had left the door ajar. I followed Jake up the steps, which were tall for a dog of my stature, crossed the threshold and inhaled.

The human odors were powerful. There were Jake’s and Mutanski’s, of course, a third that must represent their mother . . . and a fourth human, too, an adult male.

I can’t tell as much about humans from their scents as I can about dogs, but this last one was stale and unpleasant. Right away, I thought of the bad guys in the Chief stories and the humans TJ had warned me about.

My preliminary sniffing done, I looked around. In front of me to the left I saw a stairway, which I later learned led to the bedrooms on the second floor. In back was the kitchen, with a set of sliding doors that went out to a tiny patio. Ahead to my right was the living room.

And all of it was a mess!

I couldn’t help but think of the Chief stories. In them, Pierre the French chef is also maid, butler and stable hand. Rachel Mae says every well-run household needs a Pierre.

So where was Pierre now?

Sweaters, hoodies, shoes, water bottles, socks, magazines, books, papers, pens, pencils, coats and umbrellas lay wherever they had happened to fall—on the floor, the chairs, the tables or the sofa.

I like messiness as much as the next dog, but I wasn’t used to it. My early memories are of a clean bed of excelsior and my mother’s warm body and good milk, the snug feeling and familiar smells of my littermates. From there I had gone to live with my previous human, who had tidy habits and a house-cleaner once a week.

In Jake’s house, things were obviously going to be different.

“Whaddaya think, Strudel?” Jake unclipped my leash and set it on top of a pile of loose shoes by the door. “It’s not beautiful, I guess, and it’s not the Old West like where Chief lives. But it’s home, and we’ll treat you good.”

Jake’s kind voice reassured me, and I rolled over for a tummy rub—awww. Maybe the fourth human I had smelled would never come back. Maybe I’d get used to messiness. Anyway, there were lots of tastes and smells and textures to investigate.

“Come on and I’ll show you upstairs,” Jake said. It took him only a second to sprint to the top, but I looked up in dismay. A dachshund’s short legs are meant for digging, not climbing stairs.

Jake looked back and saw the trouble. “Oh, Stru, I didn’t think of that. I guess I’ll have to carry you till you’re used to ’em.”

At the top, Jake’s room was on the right, Mutanski’s (its door shut tight) on the left. Down the hall, their mom’s looked out on the front sidewalk.

None of the bedrooms was big compared to the rooms in my old home, but they were all a lot bigger than my kennel at the shelter. I wagged and woofed to tell Jake I approved.

“Do you want to play, Strudel? Is that it?” Jake asked.

Sure! Playing is good! I always want to play!

Jake tore a piece of paper from a notebook, wadded it into a ball and threw it . . . right under the bed. The floor was wood, no carpeting, and my toenails clicked as I chased it into a maze of abandoned objects, a fog of dust and cobwebs. The objects—paper plates, candy wrappers, a Pringles can—were all very interesting, but I had gone in to get that paper and I would come out with it.

We hound dogs are relentless that way. We can’t help it.

Finally I emerged with the paper between my teeth. Jake laughed. “You’re covered in crud, buddy.” He wiped my eyes and nose bare-handed.

I dropped the paper, accepted a scratch behind my ears and prepared to fetch again. But before Jake could even throw, I heard the front door open and footsteps . . . heavy footsteps.

Oh no! Oh no! Danger! A lily-livered polecat is afoot—one that’ll hog-tie us all and steal the meat right out of the fridge!

Five

I spun and barked till Jake said, “Shut up, Strudel!”

Then I spun and barked some more.

Now Jake was pleading. “You’ll get us both in trouble, Strudel. I don’t think Mom has had a chance to tell him yet.”

Tell who what? You mean Mom talks to meat thieves?

“Hey! What’s the racket up there? What is that, a dog?” asked the thief.

Jake shook his head and closed his eyes. “The man’s a genius.”

Now the heavy footsteps approached on the stairs. Jake grabbed me, dropped down on the bed and pulled me close. I smelled cigarette smoke, motor oil and aftershave lotion. Then a big man with gray-brown hair appeared in the doorway. He was wearing a green shirt with a picture of a mean-looking bird on it.

“Jee-hoshaphat!” The man locked eyes with me and shook his shaggy head. “I hope to glory you ain’t planning to keep that mutt. Your mama’s got better things to do with her money.”

The man’s booming voice reminded me of the noise on the night of the calamity. If ever there was a thieving, lily-livered polecat, this guy had to be it.

“Small dogs don’t eat much, and he’s mine, not Mom’s.” Jake did his best to sound brave, but I could feel his heart, and it was beating fast.

I let loose a rumbling growl.

“And keep him away from me, too, you hear?” the man continued.

“Are you afraid of him?” Jake asked.

“Of that thing? He’s hardly a dog at all, more like a weasel.”

A weasel, huh? I’ll show you!

With a mighty wiggle, I freed myself, jumped to the floor and made like a torpedo toward my target, the big man’s right sneaker.

“Strudel—no! Leave Arnie alone!”

Leave Arnie alone? Are you kidding? And miss an opportunity for peace and justice to triumph?

With one snap of my powerful jaws, I latched onto the shoe and didn’t let go.

But now I had a new problem. Having caught him, what to do with him? Sheriff Silver would have frog-marched this outlaw to jail. Jake’s family probably didn’t even have a jail.

Kicking and squealing, my captive leaned over and reached for something—a book from Jake’s shelf, a book to use as a weapon on me!

I cringed, anticipating the blow, but the dirty rotten varmint was so clumsy he missed, tripped over himself and almost fell to the floor.

This gave Jake time to yank me free of the shoe, which wrenched my jaw—ow!

At least no books would be hitting my head.

/> “He bit me!” cried the lily-livered polecat. “I bet there’re tooth marks dug into my flesh! I bet I’m bleeding!”

Jake said, “Look, Arnie, I’m sorry. He just got here, and he doesn’t know what’s what. You’re sorry, too, aren’t you, Strudel?”

With his thumb, Jake pushed my chin up so I looked him in the face. If he expected to read apology in my big brown eyes, he had another thing coming: Let me down! Please let me down! I want to bite him again!

I’m pretty sure Jake understood, but he played dumb. “See?” he told Arnie. “You can tell he’s sorry.”

Meanwhile, the outlaw sat down on the edge of Jake’s bed and tugged off his right shoe—creating a stink cloud that filled the room.

Bleah!

It’s true we dogs get it wrong sometimes about who’s a bad guy. We’ve been known to growl at letter carriers, police officers and even Girl Scouts. But we dogs don’t get it wrong for long. And no good guy ever had a foot that smelled that bad.

Six

I didn’t bark at Jake’s mom when she came home. Her scent reminded me of Shira’s, only with a bit more scouring powder (bleah!) in the mix. She greeted me by patting my head, but she seemed distracted. I rolled over twice, spun around and wagged my tail.

Hi! Hi! Hi! Hi! Hi! I’m your new dog! I’m so glad to be here! Hi! Hi! HI! Hi! Hi!

“He likes you, Mom! See?” Jake said.

“Unh-hunh.” Her smile was tired—too tired for enthusiasm, either for a new dog or for anything else. “Could somebody set the table, please? Any back talk and you’re toast.”

“Aye, aye, Mom,” said Mutanski, whose lipstick was now pale purple.

Arnie—aka Mr. Stinky Foot—was still around, sitting at the table in the kitchen drinking beer from a can. My previous human used to drink beer sometimes. But he always put his in a glass. “What’s the matter, sugar?” Arnie asked Jake’s mom.

“Exhausting day,” she said. “It’s tough cleaning house. You should try it and see.”

“But you’re the manager,” said Arnie. “I thought you sat behind a desk all day with your feet up.”

Goldilocks, Go Home!

Goldilocks, Go Home! Noah McNichol and the Backstage Ghost

Noah McNichol and the Backstage Ghost Effie Starr Zook Has One More Question

Effie Starr Zook Has One More Question P.S. Send More Cookies

P.S. Send More Cookies The Secret Cookie Club

The Secret Cookie Club The Case of the Bug on the Run

The Case of the Bug on the Run The Case of the Rock 'n' Roll Dog

The Case of the Rock 'n' Roll Dog Who Stole Halloween?

Who Stole Halloween? The Case of the Missing Dinosaur Egg

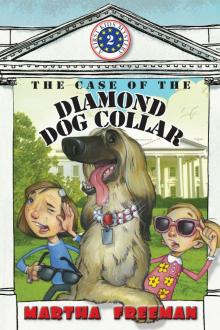

The Case of the Missing Dinosaur Egg The Case of the Diamond Dog Collar

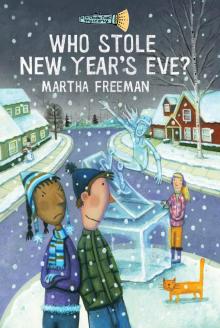

The Case of the Diamond Dog Collar Who Stole New Year's Eve?

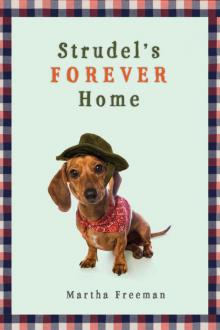

Who Stole New Year's Eve? Strudel's Forever Home

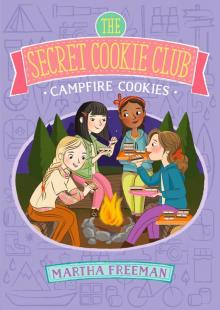

Strudel's Forever Home Campfire Cookies

Campfire Cookies The Orphan and the Mouse

The Orphan and the Mouse Zap!

Zap! The Case of the Ruby Slippers

The Case of the Ruby Slippers